The First Signal

Note from the Author

This is the complete first issue of Signals From The Machine — my monthly newsletter exploring the origins of consciousness, technology, and the human condition.

I’ve decided to publish this opening transmission here in full, so you can understand what this project is about before joining the mailing list. Future issues will only appear in excerpt form on this blog (if even). The complete transmissions will remain exclusive to subscribers.

From the second issue onward, this space (my blog) will evolve as a place for reflections, reports from exhibitions and events, and short fragments of thought that emerge between the larger works.

Thank you for being here at the beginning.

— N.H.

Dear Reader,

Thank you for joining me on this journey toward our conscious self.

This is the first issue of my newsletter.

I’ve prepared an extensive reading list that will guide me for about a year. Each month, I’ll read two or three books focused on a particular theme, and afterward, I’ll let an artificial intelligence interview me to test and deepen my understanding of the ideas I’ve encountered. The newsletter you’re reading will emerge from these conversations with the machine and my reflections about what I’ve learned.

Our journey begins at the origins of life itself - with the first sparks of self-awareness and proto-consciousness - and will continue through early animistic and spiritual explanations of existence, the Egyptian and Mesopotamian soul concepts, and the philosophical inquiries of ancient Greece.

From there, we’ll move through Eastern spiritual traditions, Western mysticism, and Christian and Islamic thought, before arriving at modern psychological and scientific understandings of consciousness, cognitive science, cybernetics, and artificial intelligence.

After that year, I’ll see where this project takes me. Maybe I’ll stop the newsletter, or dive deeper into philosophical AI topics. The world in a year will look different from the one today, so planning beyond that would be pointless.

What I hope to gain from this is a deeper understanding of who we are, what we might become, and the belief that we even stand a chance to steer the destiny of our species in a more constructive direction.

I also hope to find inspiration - for my art, for my writing, and for my work as a software entrepreneur, where artificial intelligence stands at the core of what I create.

So let’s dive right in…

🜏

For the sake of processing the following information, let’s assume there is something like the “self.” And let’s also assume that there is not only one self, but at least two of them. One of them is the objective self, the one that experiences sensations - the self that is awareness. And the other is the observer self, the one watching what is happening to the objective self.

Let’s try to identify with the observer self for a moment.

Science has uncovered that the human brain contains roughly 86 billion neurons. Neurons are specialized cells that transmit information using electrical and chemical signals. They connect with each other through tiny gaps called synapses, forming complex networks. These networks allow the brain to think, feel, move, and remember.

The cerebral cortex alone contains about 15 to 20 billion neurons and around 65 trillion connections. It is the folded outer layer of gray matter responsible for higher brain functions like perception, decision-making, language, and complex thought. It is divided into different regions that each take care of specific tasks, like seeing, moving, hearing, or planning. Functions that partly help us to describe our experience of existence.

But sensory perceptions are not limited to the cortex. Other parts of the brain play important roles as well:

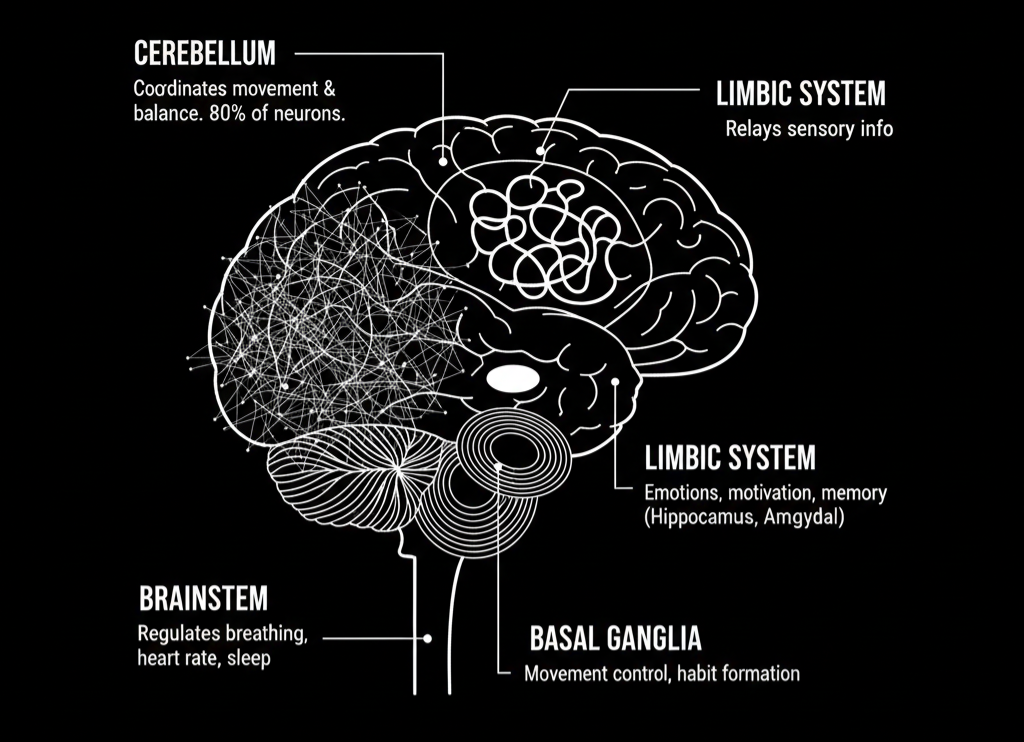

The cerebellum helps coordinate movement and balance (interestingly, it contains even more neurons than the cortex, although of a different kind). The brainstem regulates vital functions like breathing, heart rate, and sleep. The limbic system, including the hippocampus and amygdala, manages emotions, motivation, and memory. The basal ganglia help control movement and habit formation. The thalamus relays sensory information; the hypothalamus regulates hunger, temperature, and hormones.

As the observer self, we can also notice what happens to the rest of the body when the objective self experiences a sensation. The body reacts as a whole:

Heart rate and blood pressure may rise or fall. Breathing can accelerate or pause. Muscles tense or relax. Neural activity increases. Skin flushes or sweats. Pupils dilate; facial muscles express what is felt.

Every part of the body participates in what the objective self experiences as an emotion.

Once we appreciate how incredibly complex our brain and body must be in order to create these sensations, let’s make an imaginative jump. Let’s assume we are a much simpler organism - one with no words to describe what is happening inside.

The earliest life forms, single-celled organisms over 3.5 billion years ago - had no nervous system, so they could not feel the way we do. But they could respond to stimuli: moving toward nutrients and away from toxins. This is called irritability or stimulus-response behavior, a precursor to sensation.

Later, perhaps 600 to 700 million years ago, simple multicellular animals like jellyfish evolved primitive nerve nets. These early nervous systems allowed them to detect light, touch, or chemicals and react accordingly. The first kinds of sensation were likely touch or chemical detection - the presence of food or danger in the surrounding water.

These were still not “conscious” in a human sense. But they were the biological roots of it.

The earliest organisms that could feel would have felt the most basic survival sensations: hunger, thirst, pain, and lack of air.

To get a sense of how powerful and primal these feelings are, I invite you to try this with me:

Exhale fully. Empty your lungs. Now hold your breath.

Wait until it feels uncomfortable.

Then keep holding it just a bit longer.

Eventually, a strong force inside you overrules your conscious will to continue. It demands air. Homeostasis is the body’s most primal form of intelligence - the constant balancing act that keeps us alive. It doesn’t ask for permission, and it doesn’t negotiate. When oxygen drops too low, when heat rises too high, when hunger goes too far - it takes control. In those moments, the body does not care what the mind wants. It only cares that the organism survives.

This is the body taking control. It is nature telling the organism: survive.

It also gives us a simple answer to what Morrissey once asked in his song Still Ill:

Does the body rule the mind, or does the mind rule the body?

You just felt the answer to that question.

This small shared exercise allows us to empathize a little with early life - creatures that survived because they reacted to sensations that demanded action.

But it also makes us aware that this is just one small piece of the enormous mosaic of today’s human consciousness. And that the journey from that instinctive reaction to, for example, what Neil Armstrong must have felt as the first human on the Moon - is unimaginably long.

He stepped out of Apollo 11 knowing what kind of development it took to get from early life on Earth to get him up to the moon, also recognizing that he was in a place with one-sixth of Earth’s gravity, aware that his country had reached this moment in a global race with stakes that could have destroyed all life on Earth.

So let’s take a step back and visualize a timeline: From the first primitive sensations of survival to the moment a human first set foot on the moon.

As the observer self, we can now ask:

At what point did sensation become reflection?

What did it take for an organism to first realize: “I am the one experiencing this”?

This is the question I have set out to explore - knowing very well that I am not the first to ask it, not the smartest to ask it, and that the answer may remain out of reach forever.

Possibly until the day we extinguish the very consciousness that is asking.

🜏

But still we know one thing for sure, otherwise we wouldn’t be able to ask this question. Somewhere on that long timeline from gasping-for-air bacteria to Neil Armstrong doing a Moonwalk, something important must have happened.

And one of my absolute favorite film scenes shows it better than anything else. The opening of 2001: A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick.

We see a bunch of ape-men who basically live in a world ruled by instinct. They react. They survive. But they don’t really understand anything.

Until one of them picks up a bone.

He looks at it. Thinks for a second. And uses it to crush a tapir’s skull.

And suddenly the lights in his brain come on.

Boom: recognition.

The birth of intention.

And because this moment is literally the beginning of everything that makes us “us,” Kubrick doesn’t film it like a documentary. He films it like a religious event. Slow motion, massive orchestra, like the universe itself is going: “Pay attention. Something big just happened.”

The ape realizes that the bone is a tool. He can kill tapirs with it. He can smash the faces of the hostile neighbor tribe. He doesn’t become the boss of the savannah because he has the biggest muscles or sharpest teeth - the leopard wins that category in the first five minutes of the movie, he becomes the boss because he innovates.

He uses his brain to observe, process, and come to new conclusions.

If I do this → then that happens.

Cause. Effect. Welcome to the human condition.

Now he can influence his destiny. At least the tiny portion of the cosmos that currently fits into his brain.

Kubrick then does the most iconic thing ever put on film: He throws the bone into the sky - hard cut - spaceship.

First tool → most advanced tool.

Millions of years in one edit.

Absolute genius.

It’s both incredible and honestly a bit scary.

Because what he’s showing is,

as soon as we understood something, we started messing with everything.

This scene brings up a question that will follow us through this whole project:

Does consciousness automatically mean the ability to change the environment? I want to believe it does.

But like everything in this newsletter, this belief is a work in progress.

I might completely change my mind once we go deeper into the topic.

Which, honestly, is part of the fun here.

🜏

I want to end this issue with a personal reflection.

What was the sensation in my own life that made me realize I exist as a self?

I try to think back to childhood. Traveling with my parents. Playing with the dog on my grandmother’s tennis court. Good memories. But if I’m honest, the moment my mind was most brutally dragged into presence wasn’t a joyful one. It was a traumatic experience in my early teenage years.

I lost someone close to suicide. Shortly after, I was sent to boarding school, suddenly on my own. The feeling of unfairness was overwhelming.

I asked myself: “Why is this happening to me?”

Not just: This hurts. But: This hurts me.

That question was the first time I remember having an inner dialogue that referenced the self as something separate from the world. An observer formed inside me. Something watching the pain and trying to make sense of it.

Now, as a father, I witness my son collapse to the floor in tears when I tell him I need a short rest after a long day. He also finds that unfair. But he’ll forget those moments I hope. And I hope he never has to experience an “unfair” moment that leaves a mark as deep as mine. Even though, in a strange way, that moment woke me up.

That was the observer self coming into being - recognizing that there’s an objective self inside me that things happen to. The emotions were intense, but they were my emotions. And soon I discovered something even more powerful. I could change my reality.

I didn’t want to stay in that boarding school. I just wanted to be home with my family.

So I got myself kicked out for misbehavior.

And suddenly, the universe reacted to my will.

This was both powerful and terrifying. One tragedy had happened to me, but now something was happening because of me.

Over the years I learned that this force – the ability to turn thought into action – could also be used constructively. To build a career. To form a family. To design a future.

Along the way I also realized that emotions have a purpose. They are instructions. Our mind uses emotions as signals – as markers of what belongs to the self and what doesn’t. Many emotions even had evolutionary advantages. Disgust protected us from spoiled food poisoning. Fear protected us from danger. Compassion helped us to care for others, especially when cooperation increased survival.

And if we look at our senses as input devices (eyes like cameras, touch like a depth sensor etc. etc.), and brain areas like processors (CPU, GPU, memory), we can see how the brain uses the sensory inputs to simulate a map of the world. What the observer self experiences is this internal simulation. That makes it thinkable that parts of our consciousness could one day be reproduced, because computers are already quite capable of doing just that.

What I hope cannot be reproduced so easily is the part of us that forms a true will. The objective self. The part that rebels. That loves. That deserves human dignity.

That is why this project does not only study science. It will also include spiritual and religious texts. Because if there is something divine within us, I want to understand it before we give it away.

At the same time scientific research suggests that nothing about us is actually sacred. Even compassion, some say, is only emulated when it is rewarded by the group. Evolution doesn’t seem to need a soul for that.

But I’m not ready to give up hope that something more remains.

That after all the layers are peeled away, there is still something in us that cannot be explained away, replaced, or synthesized.

That is why I am writing this.

To find that spark. Because I want to believe it exists.

So let’s continue next month and ask the next question together:

If everything is alive, what does it mean to wake up?

- Transmission Sent -